Reading the Canterbury Tales, old school

After my previous encounters with the Canterbury Tales, I’ve decided to read the entire thing. As before, I think that reading a modern translation loses the interesting parts of the language and screws up the poetry, so I want to read it in Middle English. and just because I can, I’m reading (a copy of) a 600-year old handwritten version. Those are images of the Hengwrt (“HENG-urt”) manuscript, which was probably written sometime between 1400 and 1410 (note that Chaucer himself died in 1400, but it’s hard to get closer to when he was alive). The images are very high quality; click the “all sizes” button towards the top to enlarge it a bit, then the “original resolution” link to see its true glory. I wish there was a way to set the default resolution higher, but I don’t know if that’s possible.

Sure, I could read a version with original spelling in a modern font, and towards the end I probably will. but for the moment, the novelty of reading a handwritten manuscript hasn’t worn off, so I’m persisting. It took a bit of time to get the hang of the handwriting and grammar, so in the interests of helping others follow in my footsteps, here is an illustrated guide to reading the manuscript.

Letters and the Alphabet

I will write letters in uppercase to make them easily identifiable, but I’m really talking about the lowercase versions.

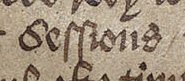

There are 3 different glyphs for S, depending on whether it comes at the start, middle, or end of a word. The one at the end looks like a modern S (though the endpoints might touch the middle part). The one in the middle of a word looks like an F without the middle crosspiece, and it extends below the baseline (this was the origin of the integral symbol, in which the S stands for “sum;” the Greek letter sigma is used in summation notation for the same reason). The one at the beginning of a word looks kinda like a modern S but more open and tilted further to the right. This word is “sessions.” Be careful not to get the middle S confused with an L, which does not extend below the baseline and has more of a hook at the top. You can compare them on the first line of the next image, which reads “my gladnesse.” There are 3 different glyphs for S, depending on whether it comes at the start, middle, or end of a word. The one at the end looks like a modern S (though the endpoints might touch the middle part). The one in the middle of a word looks like an F without the middle crosspiece, and it extends below the baseline (this was the origin of the integral symbol, in which the S stands for “sum;” the Greek letter sigma is used in summation notation for the same reason). The one at the beginning of a word looks kinda like a modern S but more open and tilted further to the right. This word is “sessions.” Be careful not to get the middle S confused with an L, which does not extend below the baseline and has more of a hook at the top. You can compare them on the first line of the next image, which reads “my gladnesse.” |

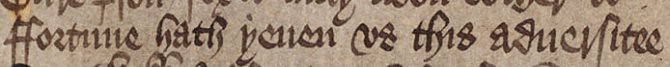

The lowercase letters N, U, V, I, and M can be tough to distinguish, because they’re all just a series of vertical lines, each with a serif to the upper left and another to the lower right. The word on the bottom line is “ffortune” (it was somewhat common back then for words to start with FF, and this spelling is still found in some names today). Notice how the F’s look just like S’s with a crosspiece through the middle (in particular, they extend below the baseline, unlike modern F’s). Getting back to N’s and U’s, the U is slightly thicker at the bottom and the N is slightly thicker on top, but this can be hard to see. The word in the middle is by far the hardest I’ve encountered so far, and it says “comune” (these days spelled “commune”). If this scares you, take solace in the fact that most words only string a couple of these letters together. Finally, note that there was literally no difference between U and V back then, so don’t try to distinguish them. The lowercase letters N, U, V, I, and M can be tough to distinguish, because they’re all just a series of vertical lines, each with a serif to the upper left and another to the lower right. The word on the bottom line is “ffortune” (it was somewhat common back then for words to start with FF, and this spelling is still found in some names today). Notice how the F’s look just like S’s with a crosspiece through the middle (in particular, they extend below the baseline, unlike modern F’s). Getting back to N’s and U’s, the U is slightly thicker at the bottom and the N is slightly thicker on top, but this can be hard to see. The word in the middle is by far the hardest I’ve encountered so far, and it says “comune” (these days spelled “commune”). If this scares you, take solace in the fact that most words only string a couple of these letters together. Finally, note that there was literally no difference between U and V back then, so don’t try to distinguish them. |

The W’s have these swoopy bits above them, so they’re very easy to identify. Y’s have a dot over them, and their tails hook to the right. D’s have a loop at the top (like a partial derivative symbol), and their bottom loop is more like a triangle than a circle. This says “wysdom.” The W’s have these swoopy bits above them, so they’re very easy to identify. Y’s have a dot over them, and their tails hook to the right. D’s have a loop at the top (like a partial derivative symbol), and their bottom loop is more like a triangle than a circle. This says “wysdom.” |

When a word starts with a U or V, it has half of the swoopy part of the W, as in this “up and down.” Again, note the way upper parts of the D’s curve in on themselves, but contrast it with the way the A is wider, lacks the angles in the bottom loop, and has a serif at the bottom right (also look at “gladnesse” above). When a word starts with a U or V, it has half of the swoopy part of the W, as in this “up and down.” Again, note the way upper parts of the D’s curve in on themselves, but contrast it with the way the A is wider, lacks the angles in the bottom loop, and has a serif at the bottom right (also look at “gladnesse” above). |

There was no distinction between I and J. This word, though spelled “ioye,” is “joy.” Luckily, J is an uncommon letter, so this doesn’t come up often. Note that although the Y is dotted, the I is not. There was no distinction between I and J. This word, though spelled “ioye,” is “joy.” Luckily, J is an uncommon letter, so this doesn’t come up often. Note that although the Y is dotted, the I is not. |

Capital I’s extend below the baseline and have this big horizontal thing in the upper left. As before, note that the L has a downward part at the top, and the W has swoopy bits in “whom I love.” Capital I’s extend below the baseline and have this big horizontal thing in the upper left. As before, note that the L has a downward part at the top, and the W has swoopy bits in “whom I love.” |

There are 2 glyphs for R, both of which are shown in this “ordre.” The second one is the most common, being a thick downstroke which extends below the baseline, followed by a thin upstroke that connects it to the next letter. The other looks similar to a modern cursive lowercase R. This form is now used in modern music as a quarter rest (the R stands for “rest,” or more precisely “riposo,” which is Italian for “rest”), so it might have an extra flourish at the bottom. As far as I can tell, these are used interchangeably, and there is no restriction on where in a word a given glyph can be used (unlike with S’s). There are 2 glyphs for R, both of which are shown in this “ordre.” The second one is the most common, being a thick downstroke which extends below the baseline, followed by a thin upstroke that connects it to the next letter. The other looks similar to a modern cursive lowercase R. This form is now used in modern music as a quarter rest (the R stands for “rest,” or more precisely “riposo,” which is Italian for “rest”), so it might have an extra flourish at the bottom. As far as I can tell, these are used interchangeably, and there is no restriction on where in a word a given glyph can be used (unlike with S’s). |

Grammar

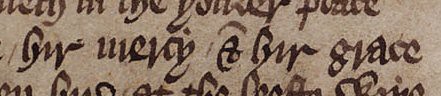

The thing in the middle is a fancy way of writing the Latin word “et,” meaning “and.” This is where the modern ampersand comes from. Note the R’s in “hir mercy & hir grace” (“hir” is now spelled “her”): if the thin upstroke doesn’t have a letter to connect to, it goes to the right a bit. |

Yes, this says “fleen.” Adding an N to the end of a verb makes it the past tense. Modern authors would spell this “fled.” Some words in Middle English add the usual ED to the end to signify the past tense; I don’t think it’s significant if a verb uses one over the other. Yes, this says “fleen.” Adding an N to the end of a verb makes it the past tense. Modern authors would spell this “fled.” Some words in Middle English add the usual ED to the end to signify the past tense; I don’t think it’s significant if a verb uses one over the other. |

Adding a Y to the beginning of a verb makes it the past participle. This says “the dores weren faste yshette” (the doors were shut tight). Again, see how “were” is made into the past tense by appending an N. Be careful not to confuse an ST with an FT as in “faste,” since although the crosspiece of the T touches the S, it does not go through it. |

This is a thorn with a superscript T, and it’s an abbreviation for “that.” Thorn is an archaic letter that was pronounced like a TH. Outside of this one abbreviation, there are no thorns in the manuscript, so you don’t need to watch out for them elsewhere. A similar abbreviation is a W with a superscript T, which stands for “with.” This is a thorn with a superscript T, and it’s an abbreviation for “that.” Thorn is an archaic letter that was pronounced like a TH. Outside of this one abbreviation, there are no thorns in the manuscript, so you don’t need to watch out for them elsewhere. A similar abbreviation is a W with a superscript T, which stands for “with.” |

Speaking of archaic letters, the letter yogh was eventually replaced variously by G, Y, GH, and W. One tricky thing I’ve seen so far is that “to give” (which was originally spelled with a yogh) is spelled with a Y here, as in “ffortune hath yeven us this adversitee.” It comes up a few other times; if you see a word with a Y that you don’t understand, try substituting a G. Note the flourish on the U in “us” because it is at the start of the word (this one goes down instead of up to avoid colliding with the Y on the previous line). Also note how adding an N to the end of yeve/give makes it the past tense. |

An apostrophe/line over a letter indicates that it is followed by an R and some sort of vowel (in either order), as in “reverence.” Which vowels are missing can usually be decided by context (E is the only one that fits in “revrence”). An apostrophe/line over a letter indicates that it is followed by an R and some sort of vowel (in either order), as in “reverence.” Which vowels are missing can usually be decided by context (E is the only one that fits in “revrence”). |

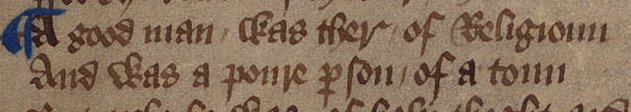

If the letter is a P, the “apostrophe” is sometimes (but not always!) written as an underline, as in “A good man was ther of Religioun/ and was a poure parson of a toun” (side note: paragraphs are denoted using a blue paragraph symbol, rather than an empty line). Recall the way U and V are identical; some scholars who study Middle English for a living claim the word before “parson” is spelled “povre,” though it still means “poor.” This older spelling makes it easier to trace to its French origins (“pauvre”), which is why I prefer the original text to a modern translation. I used the example of “parson” here because it could just as easily have been “person” or “prison.” Indeed, some manuscripts of the Tales actually say “person” instead of “parson” here, and later in the manuscript this same spelling really is used for “prison.” The missing vowels are implied solely by the context. |

| Most punctuation has been omitted because it wasn’t in widespread use yet. In particular, there are no quotation marks, so you must figure out who is speaking from the context. This is easier than it sounds because the text is written in a way that takes the issue into account, as in “Allas my lord quod she why make ye your self for to be lyk a fool” and so on. The blue paragraph markers are the main punctuation symbol. |

| Gerunds and progressive tenses of verbs are made by appending YNG instead of ING. Y’s were very fashionable at the time because they had been incorporated from the classy French, which had in turn incorporated them from the exotic Greek (the French word for the letter Y is “ygreck,” literally “Greek ee”). |

| Prepending an N to a word negates it. “Nam” is “am not,” “nis” is “isn’t,” “namoore” is “no more.” |

Spelling and Vocabulary

- If the modern spelling ends in ION, the Middle English spelling might end in IOUN (“Religioun,” above).

- If you don’t understand a word, try swapping two letters side-by-side and then changing the vowel. “Sorwe” is “sorrow,” “arwes” are “arrows,” “thurgh” is “through,” “widwe” is “widow,” and “aks” is “ask” (yes, Futurama got it right!).

- Third person pronouns are often missing their T’s. “Hem” is “them,” “her” is “their,” “hey” is “they.” This isn’t always the case: “them” and “they” also appear in the manuscript. and as mentioned earlier, “hir” is “her.”

- Contractions can be made with “thou” if the previous word ends in a T. For instance, “knowestow” is a contraction of “knowest thou.” “Hastow” is a contraction of “hast thou.”

- Sometimes words will have an E appended to the end. There are lots of reasons to do this: to denote that a word is the object of the sentence, or to denote the definite rather than indefinite form, or because the author needed an extra half syllable to make the line scan correctly. If you ignore all unexpected trailing E’s, you can read stuff just fine (though you might have the grammar wrong if you try to write). In particular, remember that “hire” often means “her,” since it’s just “hir” but used as the object of the sentence.

- Random vocabulary:

- Oon = one

- Twey = two

- Thre = three

- Prik = shoot (with arrows)

- Eek = also

- Solempne = solemn

- Moot = must

- Woot or wot = know(s), as in “God woot” or “they wot noght,” or “for wel ye woot”

- Koude = could, is able to

- Doon, dooth = various conjugations of do (done and doth)

- Wele = prosperity, related to “well” as in good health

- Wood = mad/crazy

- War = aware of, wary of

- Whilom = Once upon a time

- Soote = sweet

- Swich = such

- Clepe = to be named (“Istanbul was once ycleped Constantinople”)

- Highte = named (synonym of “cleped,” I think)

- Natheles or nathelees = nonetheless

- Wight = person

- Anon or anoon = immediately/soon

- Everichoon = everyone or each one

- Axe = ask (alternate spelling of “aks”, discussed above)

- Yow = you

- Certes = certainly

- Mo = more (perhaps Notorious B.I.G. was a scholar of Middle English?)

Further Tips and Resources

- The first few pages are much dirtier and more stained than the rest. If you have trouble with them, try again a few pages later; it’s much easier.

- I found it was immensely helpful to read aloud (remember back in kindergarten when you did this? It still works!). Reading out loud helps to sound out and recognize words, because they were written phonetically (the dictionary wouldn’t be invented until 350 years later, so people were free to spell however they wanted). Not only does reading aloud help you sound out words, it gives you a better sense for the meter of the poem, and it makes it easier to get the rhymes right when they have unusual spelling. I half want to bring up Saint Ambrose, who impressed the heck out of Saint Augustine with his ability to read silently (which was an unusual feat at the time!), but those events took place in the fourth century, and I don’t know if silent reading was still unusual a millennium later when Chaucer was around.

- Here is an invaluable guide to the prologue. It’s great because it sets things in an historical context (for instance, when the Prioresse is described as not putting her fingers in her sauce at dinner, this is a huge compliment because silverware hadn’t yet been introduced to England so everyone ate with their hands. To eat soup without getting your fingers dirty was an impressive feat indeed). This book will help you get the hang of things, and it’s very good at defining unusual words that you won’t recognize (and that I haven’t included above because they’ve only come up once so far). It’s fantastic, and I wish I could find its equivalent for the rest of the Tales. I picked up a copy on eBay, and am now the proud owner of a century-old book.

- Librarius has this great feature where you can click on certain words to see their definitions. Unfortunately, the words I really want to know about are often not clickable. but it covers the whole Tales, so it’s better than nothing.

If you have any further questions/suggestions, I’d be happy to answer them and add them above.

Now that you’ve got some idea what’s going on, here are the first few lines to start you off:

Here bygynneth the book of the tales of Caunt’bury

Whan that averyll wt his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath pced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich lycour

Of which v’tu engendred is the flour

Whan zephirus eek wt his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne

and my own translation:

Here begins the book of the Canterbury Tales

When April with his sweet showers

Has pierced the drought of March to the root

And bathed every vein in such liquor

From which the flower draws its virtue and strength

When also Zephyr, the wind god, with his sweet breath

Has inspired in every forest and glen

The tender crops and the young sun

Has run through the half of the Aries zodiac that occurs during April

and that’s why I don’t like modern translations. :-P